Riddles in the Dark: Tolkien’s Post-LOTR Edits to The Hobbit

Gollum wasn't always like this... How Tolkien’s Hobbit edits reshaped Gollum from a harmless riddle-lover to the slimy creature we know him as today

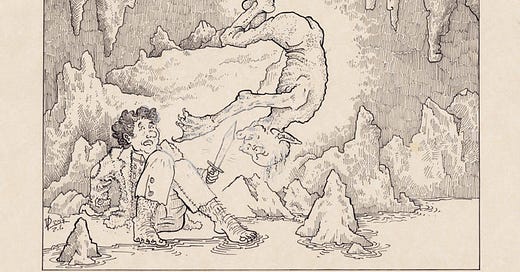

Picture from Riana-art via Deviant Art

A. J. Grant

Even some of the most knowledgeable fans of the beloved high-fantasy novels The Lord of the Rings (1954) trilogy and The Hobbit (1937) are unaware of J.R.R. Tolkien’s extensive edits to the first edition of The Hobbit. Since its original publication, Tolkien edited the first edition of The Hobbit to fit better into the narrative and world of the post-published Lord of the Rings. These edits, though not requested by the publishers at George Allen & Unwin, were instead brought on by the request of “more Hobbit content,” resulting in the subsequent trilogy, which revolves around the nephew, Frodo, of The Hobbit’s main character, Bilbo Baggins (Eveleth). These edits proved necessary to fully capture Gollum's distinctive and complex character and ultimately contributed to audiences' negative perception of him today.

Tolkien’s Gollum is a slimy cave-dwelling creature with a deep lust for the ring of power, which he calls “my precious” (Tolkien 82). The Hobbit’s first edition description of Gollum was much more lighthearted and friendly, portraying him as a riddle-speaking hermit rather than the malicious and hideous pervert of power he was in The Lord of the Rings. This edit also changed Bilbo slightly from a curious and naive adventurer to a sly thief who is unfriendly and disgusted by Gollum. However, since the original publication of The Hobbit, a lighthearted adventure novel for young readers (Eveleth), the darker post-LOTR edits bring up the question of Tolkien’s authorial intent. Through critical editing of Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark,” Tolkien went against his original authorial intention, specifically at the request of his publishers, who desired more content that would eventually convolute the previously established characters of Gollum and Bilbo.

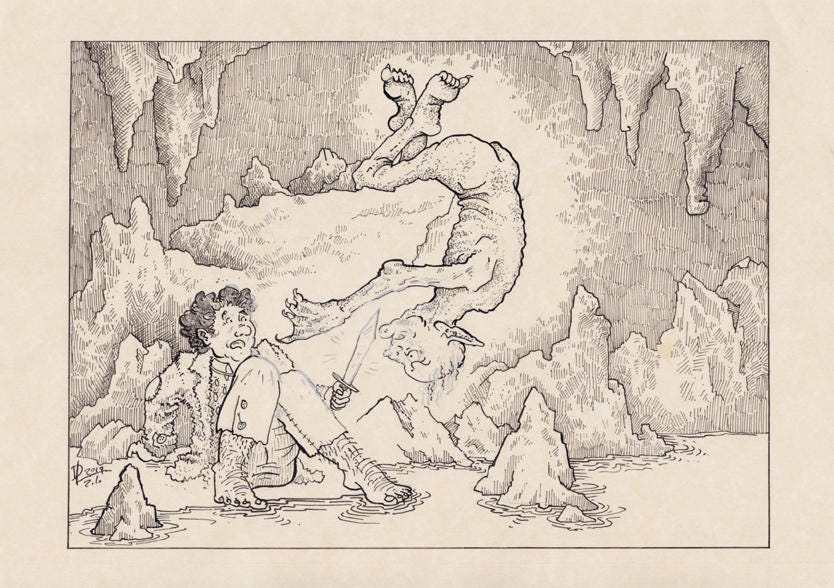

Tolkien describes an alternate version of the riddle game with Gollum in Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark.” The original and the edit stay the same for the first five pages of the chapter. After suffering a steep fall, Bilbo Baggins finds himself lost in a dark cave. He walks through the tunnel, and his nervous yet adventurous attitude strengthens him to journey to a place most Hobbits would avoid. There, he finds a pool of water, where a slimy and pale creature named Gollum lives on an island in the center. Initially, Bilbo and Gollum are hesitant toward one another, with Bilbo holding his knife out and Gollum hissing at the hobbit. However, they move to greet one another and engage in a somewhat friendly game of riddles (Tolkien, 80-84 in passim).

Here, we see the first seemingly small change, but a significant one that drastically alters the characterization of Gollum. In the first edition, Gollum suggests they play a riddle game, and if Bilbo guesses each riddle correctly, Gollum “gives it a present, gollum!” (Tolkien 85, 1st ed.) A reader with prior knowledge of the series may happen to guess that this present will be Gollum’s prized possession: the ring of power. What Gollum is not aware of, however, is that Bilbo already found the ring somewhere at the entrance of the cave in the previous chapter. The fact that Gollum, in this version, willfully offers up one of his most “precious” items is a true testament to his original character; Gollum is initially a pitiful hermit who seemingly seeks only companionship within the confines of his lonely cave. Once a visitor graces him with their presence, Gollum seems innocent and eager to make a new friend. However, Gollum’s character takes a harsher approach in the edit. In Tolkien’s edits, he offers Bilbo a passage out of the cave rather than his prized possession (85, 2nd ed.). The change in reward from one edition to the next implies that if Bilbo had not won the riddles, Gollum would have let him die in the cave with him. In this edit, Gollum is still lonely and miserable but has a more malevolent intention.

The following sections go virtually unchanged besides a few new word choices, such as changing “present” to “guess” as Gollum and Bilbo engage back and forth with complicated riddles. When Gollum stumbles over the answer to one riddle, Bilbo secretly wishes “the wretch would not be able to answer” (Tolkien 86, 2nd ed.). Bilbo’s remark are just the beginning of many more harsh comments diminishing Gollum’s original semi-helpful character. Both characters are affected by the edit, as Bilbo moves away from a naive traveler to a judgmental intruder in the cave, and the reader’s perception of Gollum is further affected by Bilbo’s internal dialogue. The audience, viewing the exchange through the eyes of Bilbo, is inclined to agree more with the main hero than with a malicious creature hiding in a dark cave. The riddle game continues unchanged between both versions, with Gollum tripping up on the final riddle given by Bilbo until he cheats by giving two answers at once. When both prove to be wrong, Gollum finds himself incorrect and embarrassed. What occurs next is the most extensive edit of the chapter. Originally, Gollum sincerely apologized for cheating and moved to retrieve his present for Bilbo. When he cannot find the ring within his chest of oddities, Bilbo suggests he show him the way out instead. Gollum leads him through the passages and is a helpful guide until “Bilbo slipped under the arch, and said good-bye to the nasty miserable creature, and very glad he was.” (Tolkien 92, 1st ed.) Though Bilbo was disgusted by Gollum and unwelcome to spend any longer in the cave, he had enough politeness to say goodbye and trust Gollum’s word as he led him through the tunnel. Then, he continued on his merry way with the ring in his pocket, unknowingly taking away Gollum’s precious.

Tolkien’s second edition edit does two things: engage Bilbo in a monstrous chase through the caves as Gollum relentlessly pursues him and establishes some minor lore about the original rulers of the ring that was not present because Tolkien had not yet established the full extent of Middle Earth before writing The Lord of the Rings. Gollum is now described in a predatory light once he realizes he has lost the challenge. He returns on his initial promise to lead Bilbo through the cave and instead, “He was angry now and hungry. And he was a miserable wicked creature, and already he had a plan.” (Tolkien 93, 2nd ed.) What was once an innocent game of riddles now turns into something straight out of a horror novel, as Gollum cannot find his ring and correctly assumes Bilbo has it. Though Bilbo is aware he has stolen the ring, his 2nd edition characterization turns him into the exact thing Gollum assumes: a thief. Tolkien’s inclusion of Bilbo’s thievery is a significant detail that carries over toThe Lord of the Rings, where Bilbo describes himself as having been seduced by the ring from the moment he held it, which would then lead him to become the very thing he was so disgusted with in Gollum: a physically deformed pervert of power. Gollum chases Bilbo out of the cave, personifying what Tolkien describes as a green-eyed and frantically hissing monster. When Bilbo uses the ring to turn invisible and elude him, Gollum yells, "Thief, thief, thief! Baggins! We hates it, we hates it, we hates it for ever!" (95 2nd ed.). We know this is not the last time we will see Gollum, but his hatred will continue decades later until he runs across his enemy’s nephew, Frodo Baggins, and continues his relentless pursuit of what Bilbo stole from him.

Here we have a compilation of significant changes in just ten pages alone: Gollum is more ruthless and malevolent to reflect his villainous character in LOTR, Bilbo is now a thief seduced by the ring of power, and the ring is provided with more lore when Gollum mentions the previous “Masters” of the ring who used to be in control over Middle Earth (Tolkien 94, 2nd ed.). With so many changes, one has to question how rapidly Tolkien’s authorial intent shifted with the introduction of the subsequent trilogy. Tolkien himself said he planned on editing the entire The Hobbit, but decided against further edits that would change his story into something unrecognizable, “saying it ‘just wasn’t The Hobbit” any longer without its playful tone and quick pace’” (Eveleth). This quote alone implies Tolkien's level of hesitation, he edited mainly for canonical reasons; Lovers of both books would find themselves confused with the character of Gollum having changed so drastically from one form to another in between the stories. The addition of new lore adds a deeper level of world-building that was not present in the original, but at what cost? Tolkien implied that the book was meant to be a lighthearted children’s book. Still, critical editing scholar Leah S. Marcus argues, “when revision (in this case: addition) is prompted by editorial pressure, does that mean it does not encode the author’s intent? In any case, it represents the text as it was received in print by the original audience- a form that many critics today find considerably more interesting than what the author may have intended” (Marcus 149). The original edition of The Hobbit was not widely printed nor received, so “original” viewers of this unedited form are rare. It is safe to assume that the newer edits of The Hobbit added more to the story and served as a more dramatic entry into Tolkien’s Middle Earth as opposed to an innocent children’s book, which older readers would find otherwise uninteresting. Nevertheless, this still goes against Tolkien’s intention with the first edition, “When we edit, we change, and even good editing… involves fundamental departures from ‘authorial intention,’ however that term is interpreted” (McGann 53). Though he edited much of the first five chapters, one could argue that any edits done to the first edition are small shifts away from authorial intent.

If Tolkien had continued with the edits, he would have gone against everything the novel stood for in exchange for publisher and reader appreciation. Though authorial intent may not be necessary in the grand scheme of the Middle Earth stories, it is undoubtedly essential to lovers of Tolkien and the innocence of The Hobbit’s first edition. Nevertheless, editing the previously convoluted characters of Gollum and Bilbo can bolster the canonicity of the series and increase reader appreciation and comprehension despite going against what the author intended for these characters.

Works Cited

Eveleth, Rose. “The Hobbit You Grew up with Isn't Quite the Same as the Original, Published 75 Years Ago Today.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 21 Sept. 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/the-hobbit-you-grew-up-with-isnt-quite-the-same-as-the-original-published-75-years-ago-today-45448681/.

McGann, Jerome J. “What Is Critical Editing?” The Textual Condition, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2021, pp. 48–67.

Nicholls, David, and Leah S. Marcus. “Textual Scholarship.” Introduction to Scholarship in Modern Languages and Literatures, Modern Language Association of America, New York, NY, 2007, pp. 143–157.

Tolkien, J.R.R., The Hobbit, 1st ed., George Allen & Unwin, 1937, London, England.

Tolkien, J.R.R., The Hobbit, 2nd ed., George Allen & Unwin, 1961, London, England.